Earlier this week I led an innovation workshop session on value propositions for CoMotion at the University of Washington. CoMotion (in their words) collaboratively moves innovations to impact by helping to create and promote entrepreneurial thinking, innovation mindsets, creative problem-solving, and experiential and team-based project learning. UW was recently ranked the 5th most innovative university in the world, and it’s always a pleasure and a privilege to be invited to participate.

Their Idea to Plan innovation workshop is geared towards UW researchers who want to commercialize their work. It focuses on the problem to be solved, the customer segment, the market reach, and the value proposition of each teams’ innovation. The final session concludes with the development of a business pitch. Throughout the process each team is supported by Entrepreneur In Residence mentors.

I’d presented on value propositions at CoMotion before, as part of their Fundamentals for Startups series. In preparing for that session I wanted to understand what different frameworks were in use, as I have found nobody seems to agree on exactly what they should include. I went through my personal files, conducted a literature search, checked out previous UW presentations and found some great examples:

You have almost certainly heard of the framework articulated by Geoffrey Moore in Crossing the Chasm:

For (target customer – beachhead segment only)

Who are dissatisfied with (the current market alternative)

Our product is a (new product category)

That provides (key problem solving capability).

Unlike (the product alternative)

We have assembled (key whole product features for your specific application).

Michael Skok, Partner at _Underscore.VC, and Entrepreneur In Residence at Harvard Business School, builds on Moore’s framework and extends the discussion on value propositions in an excellent article in Forbes. His version is a little shorter:

For (target customers)

Who are dissatisfied with (the current alternative)

Our product is a (new product)

That provides (key problem-solving capability)

Unlike (the product alternative).

Steve Blank, Silicon Valley serial-entrepreneur and academician and launcher of the Lean Canvas movement, uses an elegantly simple sentence:

“We help X do Y doing Z.”

All these frameworks are useful, but one of the things that surprised me was what many value propositions didn’t include.

What about emotional benefits? What about costs?

When I worked for PepsiCo we were trained to express our value propositions in terms of emotional benefits, and how those in turn could tap into fundamental need states. One example is Pepsi tapping into teens’ desires to forge their own identity by positioning Pepsi as the soft drink of choice, thus repositioning Coke as the default drink for adults. The science is beginning to show that all decision makers are influenced by emotional and often unconscious factors, so it makes sense that all companies consider this.

We were also taught that a value proposition answered the consumer’s question “What I get versus what I pay” – this price can be time, money, perceived risk, potential loss of face, etc.

Think about the last time you bought a car, for example.

Did you say to yourself, Wow, this car drives like a dream, I’ll take it.

Or did you think, Boy I love this car but it’s going to require a lot of maintenance and my spouse will kill me if we have to bring it in all the time. Is this a smart decision?

Neither emotional benefits nor “price” was reflected in the value proposition statements I was seeing. So I developed a version that did:

For (target customers who have a problem – include their emotional struggle)

We offer a (category you compete in/with)

That delivers (benefit – emotional or functional)

Because (reasons why they should believe you – specific proof points that differentiate you).

All that’s required is (what the customer pays in price, time investment, risk, etc.).

As you develop that one, crisp value proposition statement that will galvanize your organization and help you attract investors, you’ll want to choose the framework makes the most sense. If your audience is wedded to a particular framework by all means use it.

But don’t let that stop you from innovating and create a framework of your own, even if you have to do it in the privacy of your own office.

Six questions to consider

- What are the emotional and even subconscious benefits of your product or service? What fundamental need states can you tap into?

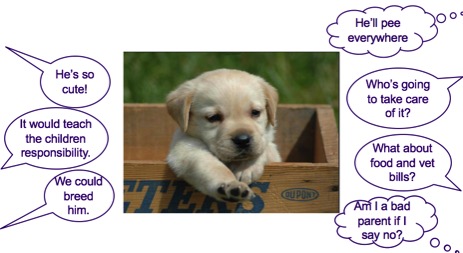

- What is the mental and emotional price you’re asking your target audience to pay, and is their internal ROI high enough for them to take action?

- How does your value proposition vary for different target market segments?

- What are the value propositions for your purchasers, end users, channel partners, and any other stakeholder groups you need to satisfy?

- What’s the value proposition for the individuals who need to say yes – your Sales team is certainly thinking about this. Are they heroes at budget time? Do they risk losing their jobs if they buy your product or service and it doesn’t deliver as expected?

- How does your value proposition change as people buy and use your product over time? Buying a gym membership is a lot different than going to the gym. Just sayin’ …

Anyone who would like to see my value proposition presentation, feel free to download it from my website. I would love to hear from any of you who are exploring this question.

This post was originally published by the American Marketing Executive Circle.